Researchers say a decades-old Canadian study that influenced breast cancer screening policy contained significant flaws in its approach, leading to a "substantial impact" on disease outcomes and potentially contributing to hundreds of "avoidable deaths" per year.

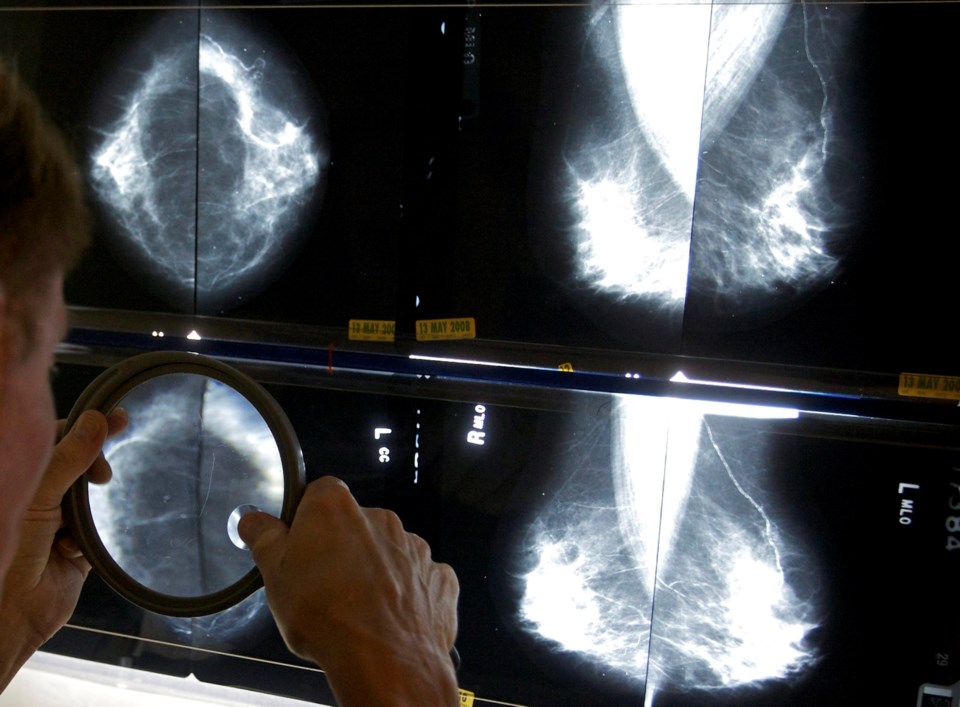

Two trials — collectively known as the Canadian National Breast Screening Study (CNBSS) — found that mammograms for women in their 40s did not reduce death rates from breast cancer.

The study was conducted in the 1980s and published in 1992.

But in commentary published this week in the Journal of Medical Screening, researchers from four Canadian institutions and Harvard Medical School say the way participants were selected for the study's control or screening groups may have influenced results.

They say more recent findings suggest there are benefits to mammography screening for women under 50, including a 2014 observational study that indicated that giving people mammograms in their 40s was associated with a 44 per cent reduction in breast cancer deaths.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care doesn't currently recommend mammograms for people aged 40 to 49, unless a pre-existing factor puts them at a higher-than-average risk — for example, if a family member had breast cancer or if they have the BRCA gene.

The Task Force said Wednesday their guidelines are "not scheduled for an immediate update."

But Martin Yaffe, lead author of the commentary and a senior scientist at Toronto's Sunnybrook Research Institute, believes change is needed. He estimated the CNBSS's influence on policy may have contributed to the avoidable deaths of more than 400 Canadian women each year.

"The idea of doing this trial was great, but the way it was designed and the way it was carried out really makes its results not credible," he said. "And basing policy on that is just inappropriate."

Dr. Brenda Wilson, co-chair of the Task Force on Preventive Health Care, said the organization's recommendations, last updated in 2018, "have been recognized as the best in the world." She added that the group conducts "rigorous, detailed evidence reviews to formulate guidelines."

"When there are substantive changes to that evidence, the Task Force updates a full review of the body of evidence, including any new evidence," she said in a statement.

The Public Health Agency of Canada issued a statement on Thursday saying it provides funding to the Task Force and referred to the body as being "arms-length from the government."

"It would be inappropriate for PHAC to direct the Task Force on which studies to include or not include in their guidelines," the agency said.

"The Task Force assesses the strength of all evidence used to develop their recommendations. The study described in the commentary is one of eight studies included in the Task Force guidelines."

The major issue with the 1992 study, Yaffe said, was that participants were given clinical breast exams at 14 of the 15 trial sites before being assigned to either the screening or control groups. That approach, he said, could inadvertently have influenced results.

He said the nurses who performed the physical breast exams assigned participants to their groups by writing their names in an open book. If a nurse felt lumps in a woman's breasts — which could have indicated an advanced cancer — she may have been more likely to place her in the screening group "in the interest of the patient, with all goodwill, but not understanding how clinical trial works."

"There was a huge imbalance in the number of advanced cancers that were found in the mammography side of the study compared to the control side ... so (the study) found no benefit of screening," Yaffe said.

"In fact, they found more women died on the mammography side than on the control group, which was bizarre because every other study in older women had shown a benefit of mammography."

Yaffe said he suspected the study's methods had been unsound for years, but the "smoking gun" only came this March when eyewitness testimony from a staff member at one of the trial locations confirmed that the randomization may have been flawed.

The size of the study — nearly 90,000 participants — gave its findings weight, Yaffe said, which is one reason it may have influenced policy across the globe.

"But if the trial was done poorly, if it was done a long time ago using approaches that are no longer being used, it may not be relevant," he said.

PHAC said mammogram screening policies fall "under the purview of the provinces and territories." Jurisdictions can use the Task Force's guidelines, but they also set their own screening programs.

Ontario, for example, doesn't screen patients under 50 but Nova Scotia residents between 40 and 49 years old can self-refer for annual mammograms. British Columbia says it "encourages" people aged 40-49 to talk to their doctor about the benefits and limitations of mammography. If screening is chosen, it is available every two years.

Jurisdictions will screen high-risk patients under the age of 50, and people who suspect something is wrong can get a mammogram referral from a doctor.

Dr. Jean Seely, co-author of the most recently released commentary and head of breast imaging at the Ottawa Hospital, said policy should be updated to allow all women 40 years or older to undergo screening mammograms.

"Screening saves lives," Seely said in a release. "There is a 98 per cent five-year survival rate for localized breast cancer when it is detected early."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 25, 2021.

Melissa Couto Zuber, The Canadian Press