2020 tied the planet’s record for the hottest year recorded despite a record drop in greenhouse gas emissions caused by the pandemic, researchers say.

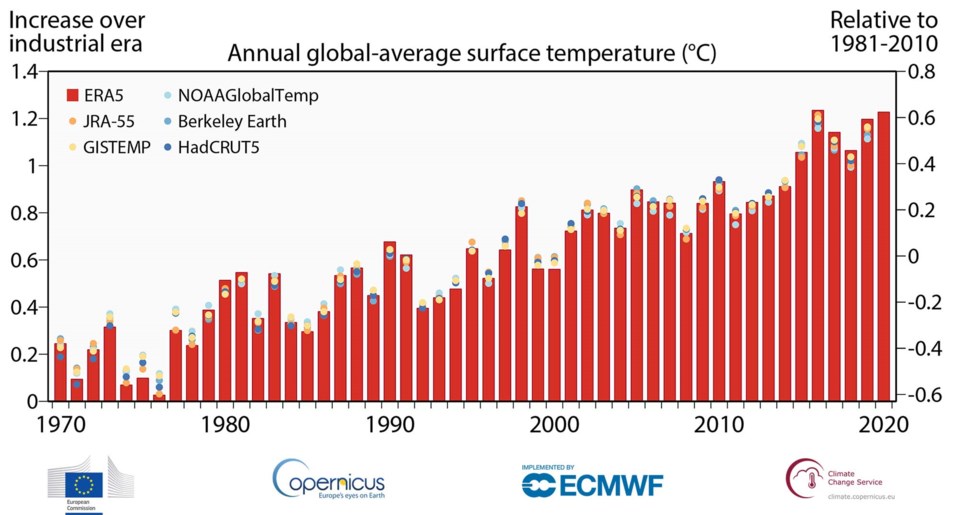

The European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service reported Jan. 8 that 2020 had tied 2016 as the hottest year on record globally, with temperatures averaging 1.25 C above pre-industrial levels. It also found that the last six years had been the hottest six years on record.

The group noted this warming is due to rising greenhouse gas emissions, the concentrations of which reached an unprecedented 413.1 parts per million despite a record seven-per-cent drop in fossil fuel-related emissions – a drop attributed to pandemic-related restrictions.

This temperature record is even more remarkable when you realize we had a cooling La Niña event last year and a warming El Niño in 2016, said senior Environment Canada climatologist David Phillips.

“One could argue this year was actually tempered somewhat by the cold La Nina, and it still became tied for the warmest year on record.”

While he hadn’t crunched the numbers for all of 2020 yet, Phillips said some parts of Canada were clearly well above normal temperatures last year, with northern Canada having its sixth warmest year in 73 years. This winter in Alberta has also proved exceptionally warm, with December and January temperatures “absolutely on fire” five degrees above normal and melting snow during what should be the coldest part of the year.

“It’s almost been winter missing in action,” Phillips said.

Warming impacts

Phillips said a warming climate effectively loaded the world’s climate dice to make extreme weather more likely. You’re not going to get sandstorms in Ottawa, but you might get one-in-100-year storms happening every 25 years.

A 2018 study by the City of Edmonton found climate warming would roughly double this region’s risk of urban and river flooding by 2050, for example, and make wildfires, freezing rain and high winds more likely.

Phillips also discussed a phenomenon called “blocking,” which some researchers believe could become more common under a warming climate.

Phillips said the jet-stream has become weaker and wobblier due to warming, allowing weather systems to stick around regions for longer to spread misery (“blocking”). When that happens, you get situations like what happened around Edmonton last spring and summer, where it rained for 81 out of the 123 days of summer, flooding bike paths in St. Albert and drowning crops in Sturgeon County.

"It was kind of just really miserable,” Phillips said, especially since much of that rain fell on weekends.

Land-use changes meant these extreme weather events would become more costly, Phillips said. Calgary has had floods before, for example, but a flood today is much more expensive than in the past because it has far more homes and buildings to be flooded. (The 2013 flood in southern Alberta was the third most damaging weather event in Canada since 1983, Natural Resources Canada reports.)

Climate action

The Copernicus group noted that the world would need to get its net CO2 emissions down to zero if it wants to stop further climate warming.

St. Albert is still far from that point, being net positive in terms of emissions to the tune of 924,884 tonnes in 2019, the city’s environment office reports. The City of St. Albert has made significant gains as a corporation, however, having cut its carbon emissions by 11 per cent relative to 2008 as of 2019.

St. Albert environmental manager Christian Benson said the city has some exciting projects coming up this year to reduce emissions. Crews would install an energy-efficient ice-resurfacing system in local arenas, for example, and add LED lights and solar panels to Servus Place. Studies on a proposed 15-acre solar farm and a program that would let residents pay for home energy retrofits through their taxes are in the works, as is a rewrite of the city’s greenhouse gas emission goals.

In addition to reducing emissions, cities have to start adapting to climate warming by passing policies that guard against the higher temperatures and extreme weather to come, Phillips said. That might mean bans on building in a floodplain, for example, or preserving wetlands to prevent floods.

“You can’t prevent it from raining, but you can prevent a flood,” he said.

The Copernicus report is available at bit.ly/2Xzb5MN.