If you’ve been paying attention, you’ve probably noticed that our climate is changing.

Maybe you were tipped off by how Ice On Whyte keeps melting in the heat of January, or the invasion of the mountain pine beetle. Perhaps you’ve spotted flowers like the prairie crocus blooming two weeks earlier than normal, or felt the icy grip of the polar vortex last February.

“When I was a kid we used to get rain for four, five, six days,” recalled Hugh Donovan, a lifelong St. Albert resident and the former head of the City of Edmonton’s pavement lab – now it comes in massive thunderstorms that flood streets and strain infrastructure. We're also seeing chinook-like temperatures around here during winter, which puts more temperature stress on roads and bridges.

“It’s those kinds of things that wreak havoc on infrastructure.”

Unseasonable heat and weird, wild weather – both hallmarks of a warming climate, say researchers. And if our climate is changing, our cities, which were built for a past climate, have to change with it. Engineers and planners like Donovan across Canada are now scrambling to figure out how to do so to meet the challenge of climate change.

The changes ahead

Donovan has spent decades studying the effects of climate change on city infrastructure and was one of the many contributors to the Climate Resilient Edmonton report. Released by the City of Edmonton last November, the Climate Resilient report is likely the most comprehensive look yet at this region’s future under climate change.

Mel Reasoner and his team at Climate Resilience Consulting did most of the analysis behind the report. They took data from 12 different global climate models and downscaled them to fit the Edmonton region to get their results, which Reasoner said should also apply to St. Albert as the two communities are so close together.

The Edmonton region has warmed some 1.7 C in the last century, Reasoner’s team found. That warming is largely due to the rising level of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the air over the last century, Reasoner explained, and has made our weather less predictable: heat is energy, and more energy means more wild weather shifts.

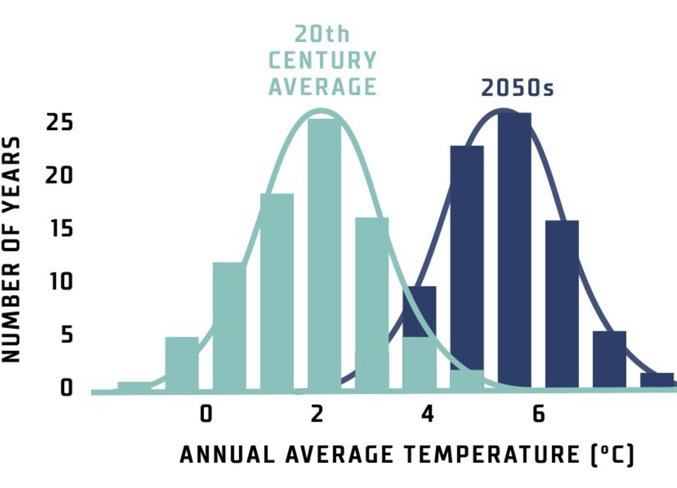

The average annual temperature in Edmonton is now about 2.1 C, Reasoner’s team found. Given current rates of emissions growth, that’s likely to more than double to 5.6 C by 2050 and almost quadruple to 8 C in 2100.

“Your average year in the 2050s will be similar to the very warmest years in the 20th century,” Reasoner said.

Reasoner’s team found that this region was on track to see hotter, drier summers and warmer, wetter winters due to climate change. They found that we were likely to have about 16 days of plus-30 weather a year by 2050 (up from one a year now), with our days below zero set to drop to 77 from 96. Annual precipitation was set to rise about 11 per cent (50 mm), most of which would come in the spring and fall.

We also have more extreme precipitation. The Climate Resilient report says that we’ll get up to 118 mm of water each year from very heavy rains by 2050, up from 96 now. More heat energy in the atmosphere will also raise our odds of extreme weather such as wildfires, high winds, thunderstorms, freezing rain, and rain on snow.

What it means

St. Albert engineer Joel Nodelman has studied climate change adaptation for about 30 years and helped develop the protocol for evaluating climate change infrastructure vulnerabilities used by Engineers Canada.

Our infrastructure systems are built to handle past climate conditions, and those conditions are set to change a lot, Nodelman said. An average shift of three degrees implies spikes of up to five or six in any given year, and when temperatures change that much, it’s anyone’s guess as to how your infrastructure will react.

“As an engineer, that’s scary,” he said.

While Edmonton will eventually see slightly fewer freeze-thaw cycles by 2050 due to warming, we’re likely to see more cycles in the near term as we shift into that warmer climate, Nodelman said. That means more potholes and repair costs.

More short, sharp storms will mean more urban floods like the ones along Perron Street in 2007 and 2008, Nodelman said. The Climate Resilient report predicts that this region’s risk of urban flooding will double by 2050 under climate change.

“We’re now looking at the potential for plus-30 regimes for extended periods,” Nodelman said, which makes drought and wildfire more probable.

Climate change can also cause health problems. The Climate Resilient report forecast some 22,000 more adverse health episodes in Edmonton a year by 2050 due to heat, drought and freezing rain, resulting in 2,400 lost years of healthy life.

Fewer days of below-zero weather would definitely mean less skiing on snow in St. Albert, said St. Albert Nordic Ski Club member Laurie Hunt. Skiers have noticed a lot more slush and ice due to temperature swings in the last five years, and are having to go higher up in the Foothills for good snow.

Hotter, drier summers with more extreme winds will be tough on St. Albert’s trees, said St. Albert parks and open spaces manager Louise Stewart. High winds are already blowing down trees in the Grey Nuns White Spruce Park, and more heat could mean less water available for trees. That means more dead trees, and more money spent replacing and watering them.

These impacts carry costs. The Climate Resilient report predicts that Edmonton could lose $8 billion a year due to health, financial and environmental costs of climate change by the 2050s, rising to $18.2 billion a year by the 2080s.

What to do about it

It’s not all bad news, the Climate Resilient report suggests. The growing season will be 24 days longer by 2050, for example, and we could see more people outside walking and riding bikes. Stewart notes that the warming so far has let St. Albert introduce new trees like the spectacular autumn blaze maple that previously couldn’t handle our climate.

But if we want to take advantage of these positives, we first have to offset all those negatives.

Step one is to reduce the scale of the change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, such as through electric buses, solar panels and net-zero homes. Reasoner’s team found that Edmonton would see just 3.5 C of warming by 2100 instead of the 5.9 that’s in the pipe now if the world made strong reductions in emissions by 2050, along with smaller changes in precipitation and extreme weather.

Step two is to do a comprehensive review of your climate risks, Nodelman said. Most of the pipes, roads, trees and buildings of today will still be around in 2050 when the bulk of climate change arrives. Can they take the change? If not, when and how should we upgrade them?

St. Albert is just starting this process, said St. Albert environmental manager Christian Benson. Crews are looking at how climate shifts will affect roads and stormwater systems, and have partnered with regional governments and the All One Sky Foundation to study impacts to drinking water, trees and invasive species.

Stewart said her crews were starting to plant more drought-tolerant species in preparation for climate change. Alberta Agriculture scientists were also testing seeds from the white spruce forest to see where they would grow best under a warmer climate.

City of St. Albert utilities and environment director Brian Brost said his department is now updating its engineering standards for stormwater pipes to reflect future precipitation trends, and planned major sewer upgrades in Sturgeon this year similar to the ones done along Perron Street in 2017 to prevent future floods. Crews have also started cleaning catch basins in advance of major storms to reduce flood risks.

Edmonton-area road engineers are now using the latest climate data from NASA to design and study bridges instead of the 1960s-era stuff they used back in 2005, Donovan said. They’re also designing tougher road bases fit for a warmer climate, and adding polymers to asphalt mixes for greater flexibility.

Homeowners can also adapt to climate warming, Reasoner and Nodelman said. If floods and wildfires are more likely, you might want to have an emergency kit ready and check for effective drainage around your home. Better air-seals and insulation can guard against temperature swings and forest fire smoke, and will also save you money. Benson said the city is working with All One Sky to create a virtual show home to illustrate other ways people can adapt to climate change.

Nodelman said it’s tough to put a price tag on adaptation (as most cities are tight-lipped on the subject), but said cities can do most of it within an existing budget with minimal impact. The Climate Resilient report said it cost zero to five per cent more to build a new house, bridge or transmission line that was adapted to climate change – much less than the cost to repair the damage a conventional one would get from climate change.

Donovan said it’s tough to convince people to spend money on adaptation, because if it’s done right, you won’t notice any difference. But if we don’t, we’ll just keep building cities the way we always have and wonder why everything keeps breaking.

“Is it money well spent? As an engineer and a taxpayer, I think it is, but the return on investment isn’t something you see.”