Toxic Theories

This is the second of two parts examining the impact of conspiracy theories on families as well as the psychological and sociological factors behind them. You can read or listen to the first part here.

Listen to an audio version of this article here:

Alyssa Anderson was raised steeped in conspiracy theories and has seen the danger of them first-hand throughout her lifetime.

Anderson, whose name has been changed due to the sensitive nature of this story, was introduced to conspiracy theories when she was just six years old, when her grandfather left his radical reading materials around for her to find.

"I just absolutely get sick to my stomach when I see conspiracy theories because I know the damage that they do firsthand," Anderson said.

Anderson told the Gazette she was raised in an ultra-conservative home and said the literature she was reading at her grandfather's house meshed in with the ideas that were being talked about around her and confirmed her worldview.

"When you're introduced to it, you just assume it's correct. Even at that age, it appeals to a confirmation bias," Anderson said.

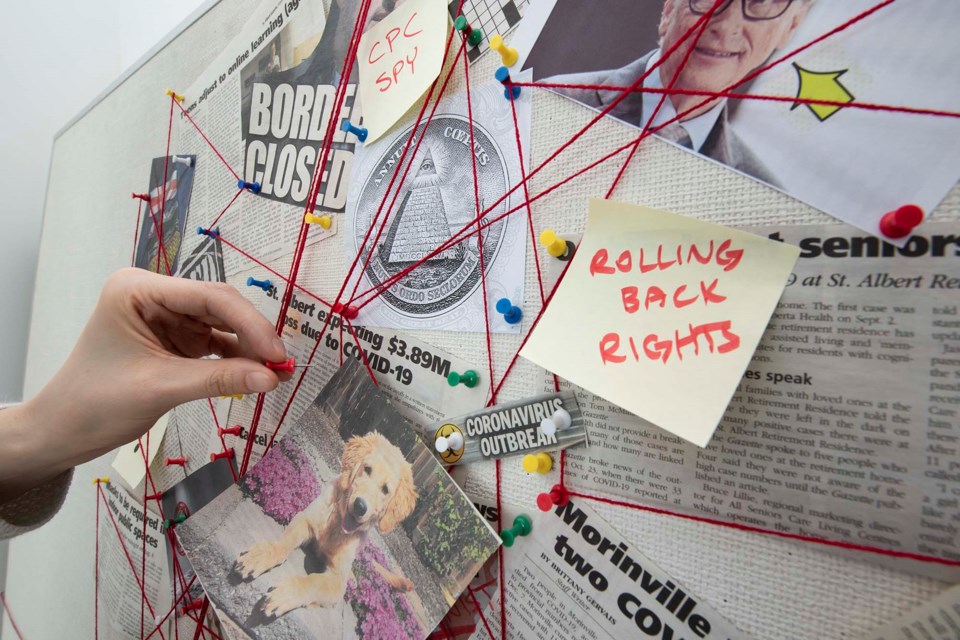

As a young child, Anderson was introduced to theories like the John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy, Rosicrucian theories, the Illuminati, the Freemasons, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and other race-based conspiracy theories.

The now-rural Alberta pastor said these theories engulfed her reality from a young age. Believing in them made her feel as though she had special information that nobody else was smart enough understand. As she grew up, her parents started to believe them more because Anderson was such a prolific reader, and they assumed their daughter was well-informed.

Then, at the age of 17, while Anderson was driving down St. Albert Trail, she had what she calls a "classic epiphany."

"You can say God spoke to me. I just had a moment of the most brilliant, blinding illumination," Anderson said, adding she suddenly felt the theories were rooted in pride, ego and half-truths.

"It gave people a superior sense of having superior knowledge and everybody else was just stupid ... It was just wrong to have that kind of attitude," Anderson said.

She realized the theories were based in fear, Anderson said, and the ones focused around race were not based in God's perfect character of love; she had been reaching for small details to confirm her biases, but many of the theories she believed were based on half-truths. Many of these reasons were how her grandfather came to believe in the theories to start with.

Getting hooked on conspiracy

Anderson describes her grandfather, who lived in Washington state, as a "happy-go-lucky man" who stumbled into conspiracy theories during a vulnerable moment in his 30s, when he was rejected by his church.

Anderson's grandparents were accused of trying to take over leadership of the church, which Anderson said wasn't true. That accusation led to them being ostracized from their community.

"It was so hard on my grandpa and he became very bitter and disenfranchised. He was a sitting duck for something to make sense of his reality," Anderson said.

Soon, a friend swooped in – like a vulture, Anderson said – and introduced him to extreme theories.

Her grandfather fell deeper and deeper into conspiracy theories during the course of his life and as he did, he brought his wife and family into that world with him.

Wedge in the family

After Anderson had her epiphany, she suddenly found herself an outsider in her own family.

One of her closest relationships with her cousin was severely impacted by the revelation, who believed Anderson had been brainwashed. Some other members of her family also stopped believing in the theories, and since then there has been a wedge in her family.

"They cannot be reasoned with. You have to make a willful decision to quit believing in them because conspiracy theories operate in the realm of possibility. So as long as there is a possibility, it could be true," Anderson said.

Within her religious community and on social media, specifically Facebook, Anderson is exposed daily to conspiratorial ideas. Right now, she noted COVID-19 theories are particularly popular.

"I'm utterly surrounded by it," Anderson said, adding she sees a lot of anger and rage online with much of it directed toward the government for introducing COVID-19 measures.

Information free-for-all

Geoff Dancy, associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Tulane University in New Orleans, who teaches about conspiracy theories, said they are extremely common and a result of people trying to make sense of the world around them. Humans are always trying to find order and patterns in the world, Dancy explained.

These theories are similar to other social science theories in that they are a way to find causal explanations in the world, but differ because they describe events as having individual human causes and they usually include a small group of people engaged in a secret plot that benefits them at the expense of society.

"'They're pulling the strings. They're doing something that is shadowy, and they're causing a lot of the things that we see in the world, but we don't see that they're causing it,'" Dancy said.

While such theories have circulated for years, right now with an infinite amount of information to consume on the internet, extreme ideas are the ones that get the most engagement while moderate or centrist ideas are less likely to get clicks and retweets.

"The current information environment lends itself to this kind of sensationalism, and conspiracy theorizing plays a part in that for sure," Dancy said.

People who fall in the middle of the political spectrum are not immune from them either, Dancy said, because you don't want one side that you might favour less to win.

"You do eventually click on things that scare you," Dancy said.

Conspiracy theories feature prominently in the plots of many popular movies, superhero movies, comic books and action movies – the bad guy is often a person or a small collection of people trying to take over the world.

At times when society is facing a high degree of uncertainty and anxiety, like during a global pandemic, and there is access to uncurated information, Dancy noted conspiracy theories can grow and spread quickly. Right now theories related to COVID-19 are thriving along with the QAnon theory, which Dancy said is the “top dog” right now due to its ability to explain “a tremendous amount of things at once” along with former U.S. president Donald Trump’s involvement with the theory. Dancy said the QAnon theory may fade now that Trump is out of the spotlight.

Societies with a high degree of individualism are also more susceptible to conspiracy theories, Dancy said, with the United States – arguably the most individualist society in the world – having a high rate of belief in conspiracy theories.

Dancy said having a high rate of belief can be an indicator that the society has less trust and social cohesion.

"Individualism and industriousness are two quintessential American traits, and conspiracy theories are built on both of those things," Dancy said.

"We think that we can come up with the best theory for what's going on, but we also blame it on other individuals."

Unfettered market capitalism can also help breed the theories, Dancy said, because there is a political economy of conspiracy theories and people are making money off of them.

Although it might feel like we are living in a golden age of conspiracies, Dancy said they have been present in society for a long time, with evidence of conspiracies present in historical events like the Salem witch trials and the founding of America.

"We're sure that this kind of stuff goes back to ancient times but it might have made more sense, in some cases, because there were single rulers whose decisions shaped all of policy and the way that society was organized was very top-down back then," Dancy said.

Jaded idealists

It is possible for anyone to believe in the theories, Dancy said, but it is generally people seeking simple solutions to big problems.

"(They believe) that there's one group or one person, or a small group, that is responsible for everything right now."

Believing in conspiracy theories comes down to psychological and societal factors and Dancy said there are generally not a lot of specific demographics that correlate to belief in conspiracy theories.

"It's just a very human thing. I try to resist the notion that there's a specific group that's more prone to it," Dancy said.

The professor said both sides of the political spectrum are susceptible to believing in a conspiracy theory, as long as if fits your world view. Some 45 per cent of Democrats in the U.S. thought that the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Centre were a conspiracy, while 40 per cent of Republicans believed that former U.S. president Barack Obama was born outside of the country.

Dancy said conspiracy theories can be partisan in nature, but that doesn't mean one side of the spectrum is more prone to believing them.

Research shows there may be three broad categories of people who may believe more in conspiracy theories, including people who are less politically engaged, who are anti-institutionalists and who think voting doesn't work.

People with less wealth generally believe in these theories more often, and members of Generation X born between the years of 1965 and 1980 are more likely to believe because they grew up in a post-war world. The United States was respected world-wide, and that all collapsed during the Vietnam War, when John F. Kennedy was assassinated, and during the race riots.

"That group lived through the breakdown of trust in the belief in American institutions," Dancy said.

Overall, conspiracy theorists tend to be "jaded idealists" Dancy said – people who want quick fixes for complex societal problems that in reality took hundreds of years of history and the construction of complex societal structures to create. These theories revolve around the idea a small group of individuals is to blame for a problem, and if those individuals are removed, the problem will go away too.

People attribute the negative impacts of a structure or institution to a small group of people, rather than recognizing the years and years of small changes to institutions that have left people feeling disadvantaged or disenfranchised.

"It's like structures and institutions that are at fault and the design of those things over time, which was never designed in one particular moment, but it happens like a sedimentary rock, it's just layers and layers of design over time," Dancy said.

"It's way easier to blame single people or single groups for that."