They’re two issues Malinowski has struggled with for years, and they’re ones an ever-increasing number of Albertans are facing.

Malinowski has been diagnosed with major depressive disorder, along with anxiety issues. Part of the way he deals with those is to find positives to focus on.

He’s developed a toolbox of positive measures against panic attacks, depression and anxiety. Sometimes, the best tool is having one of his dogs on his lap, the weight and comfort helping to calm him; sometimes, it’s being mindful about his breathing. Recently, he added a new tool to that collection: a text messaging service endorsed by Alberta Health Services called Text4Hope, a free service providing three months of daily cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)-based text messages written by mental health therapists.

The first message came to him as he was waiting in St. Albert, wishing he was back in Thunder Bay with his partner. Little things kept happening to get in the way of his return: “I should have been gone, back already, but then the furnace crapped out,” he said. “I was starting to get down again.”

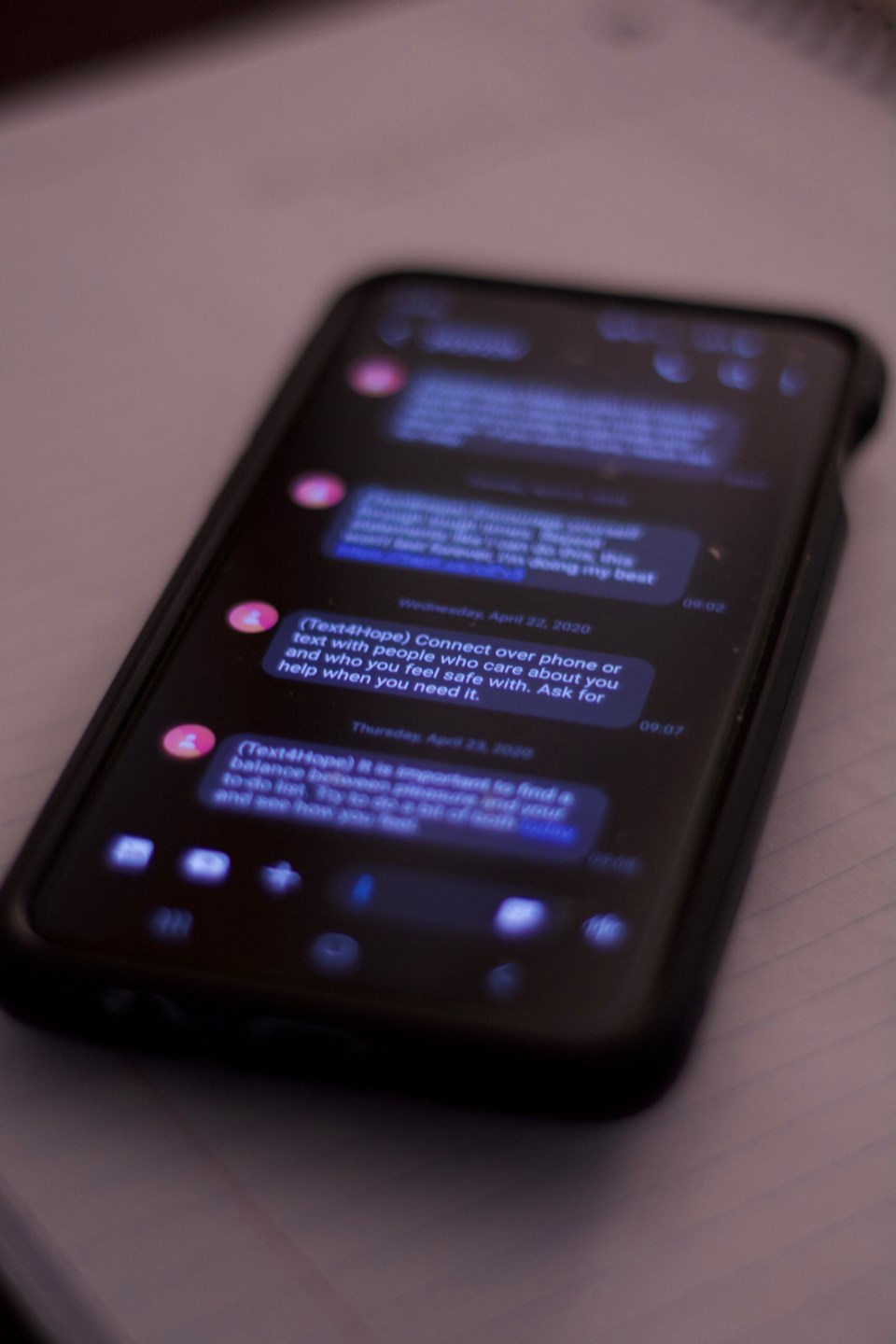

The text that appeared on his phone said, “When bad things happen that we can’t control, we often focus on the things we can’t change. Focus on what you can control, what can you do to help yourself (or someone else) today?”

“That just put me right back into focus,” he said.

“It just allowed me to say, ‘Yeah, I can’t control that. Let me just deal with it, do the things I can control, and I’ll get back.’”

Signing up for the program is as simple as texting COVID19Hope to 393939. Once you do, you’ll get a text every morning with a positive message. The idea is to build coping skills and provide support specifically during this pandemic.

“Every day, I just look forward to reading that little message ... Sometimes it links to something else, and sometimes it’s just a message that I need: ‘OK, get yourself back on track here – it’s not the end of the world. It’s bad, but we’re going to get through this,'" Malinowski said.

Text messaging support

Text4Hope isn’t a new idea in Alberta. Dr. Vincent Agyapong, the brains behind the program, ran a similar text messaging service during the devastating Fort McMurray wildfire in 2016. That service, Text4Mood, had 4,111 active subscribers.

When Agyapong’s team evaluated that program, based on a cross-sectional survey of 894 subscribers, they found it boosted the mental well-being of most respondents and helped them feel they could bounce back from mistakes. Seventy-five per cent of the people who took the survey said they felt supported by the messages.

Although COVID-19 isn’t a traditional trauma like a natural disaster, Agyapong says the scale and impact of the virus on the global economy and on society has traumatic implications for almost everyone.

“The preliminary data that’s coming through ... about 53 per cent of those who are subscribing to the program (are) actually meeting that criteria for generalized anxiety disorder for moderate to severe type,” said Agyapong, who is a clinical professor in the University of Alberta’s department of psychiatry.

“The messages (in Text4Hope) essentially have been created specifically targeting stress and anxiety and depression around the COVID-19 crisis. So it is very specific to the times.”

So how does a simple text message, mass-texted to thousands of people, have such an impact?

The messages are designed to interrupt lines of negative thinking, Agyapong says. It gives people something positive to focus on, even if just for a minute.

“If you have that coming in ... on a daily basis, the expectation is that over time, you think less and less and less of the negative things, and then develop more positive ways of evaluating situations,” he explained.

Sam Fitzner, the communications lead for the Edmonton-based Mental Health Foundation, told the Gazette at the beginning of April that Text4Hope had already seen more than 30,000 people sign up. Having messages come directly to your phone, often accompanied by a link with more information, reduces the barriers to access mental health support.

“Especially if you are struggling with your mental health, doing basic tasks can be difficult. So adding a bunch of work to get the help you need will cause a lot of people to not get help,” Fitzner explained.

It isn’t a cure-all, though. Agyapong agreed the text messaging service can be used as part of a care plan or alongside other tools to improve mental wellness.

“If you look at even the first text message that people receive, it includes a number for the crisis line,” he said.

“You don’t forget about all the other traditional resources, but what we know is that because of this, there’ll be less need for the traditional resources – at least a fraction of people who would have contacted the crisis line may not need to.”

What does the research say?

In 2014, the University of Alberta School of Public Health released a report titled Gap Analysis of Public Mental Health and Addictions Programs.

That gap analysis found roughly 20 per cent of Alberta adults – or more than 600,000 people – experienced an addiction or mental health problem in 2012. Nearly half didn't get the health care services they needed, and most programs and services that were surveyed for the analysis said they didn't have the resources to accommodate all the people seeking help.

More recently, last October Statistics Canada released the results of a 2018 survey on mental health, which showed some 5.3 million people country-wide – 17.8 per cent of Canadians aged 12 and older – needed help with their mental health. Nearly half reported that their needs were unmet or only partially met.

Agyapong believes text messaging presents a way to close the treatment gap for mental health patients. The ability to self-subscribe also means less hoops for people to jump through to get help.

"When people are struggling, they need help and they need help now," he said.

Fitzner said ideally, a solution like text messaging would be a two-way conversation, instead of the one-way texts presented by Text4Hope. However, the cost for Text4Hope works out to about $4 per person for three months of messaging, whereas a two-way conversation would require hiring full-time people to answer calls.

"We are limited in terms of cost to do these one-way texts, but I think people really want that peer support," she noted.

"I think that's kind of where technology and mental health (are) at a standstill, because obviously we have to find these opportunities that are low-cost in an underfunded sector."

Still, anecdotally, the simple act of receiving a supportive text is helpful for some. Fitzner points to feedback Agyapong's Text4Mood program received.

"Something we heard from some of the people using it was that because it came in that text format, it felt like someone was checking on them every day, because not everyone has a large extended network of friends and family depending on how isolated they've become in their mental illness," she said.

Evaluating Text4Hope's success

When you sign up for Text4Hope, you get a link to a survey designed to measure your level of anxiety, depression and stress.

The team behind the program had more than 4,000 responses in just two days, and more than half of respondents appeared to have developed a fear of contamination shortly after the pandemic broke out, Agyapong said.

The team is working with four validated self-report scales to measure that success. Those include a perceived stress scale that measures people’s perception of how much stress they are under when they’re in a crisis; the PHQ-9 scale, which is commonly used to screen people for major depressive disorder; the GAD-7, which measures generalized anxiety; and elements from the Brief Obsessive-Compulsive scale to look at people’s fear of contamination and their tendency to wash their hands repeatedly.

Beyond that, Agyapong said the team is also evaluating people’s satisfaction with the system in general.

Agyapong said the survey is repeated at six weeks and at 12 weeks.

“We can actually be able to correlate the responses when they sign up with their responses at six weeks and at 12 weeks, which will give us very valid, in-depth metrics to measure the impact of the program,” he said.