St. Albert resident Christine Brown knew her son Tyler (names have been changed to protect their identity) was struggling in school, but neither she nor his teachers knew what the problem was until he was in fourth grade.

"He would sit in class and one teacher said to me, 'I know he's listening. And I know he's learning,' but he would have no output. No written or verbal output. He was really good, but he would have no written output at all," said Brown.

Tyler was eventually diagnosed with developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD) or dyspraxia. Although it is a common neurodevelopmental disorder which affects movement, it isn’t a condition that is well known, well understood, and can sometimes be missed altogether.

It is estimated around five to six per cent of children have the condition, said Caitlin Hurd, a physiotherapist at Summerside Children’s and Sport Physiotherapy who works with children who have DCD.

The symptomatic manifestations of DCD are as individual as the people impacted by it and not much is known about why it occurs.

The disorder usually becomes apparent in the classroom when the child is around others their age.

“Sometimes [parents] have some idea and other times they're like, ‘Oh, I thought they just didn't enjoy sports,’ or those sorts of things,” said Hurd.

People who have the condition may have issues with fine- and gross-motor skills, motor planning, and co-ordination. They may be clumsy and have issues with sitting, standing, or walking.

Children can have problems with writing, zippers, and tying shoes. They might retreat when it comes time to doing anything physical.

Brown said Tyler was always tripping.

“Other kids, probably much younger than him, are running through the playground, no problem. He's walking and he does a face plant … When he would fall, he didn't put his hands out to stop, he just would fall,” she said.

Fine-motor skills, such as writing, can be particularly difficult for kids with DCD.

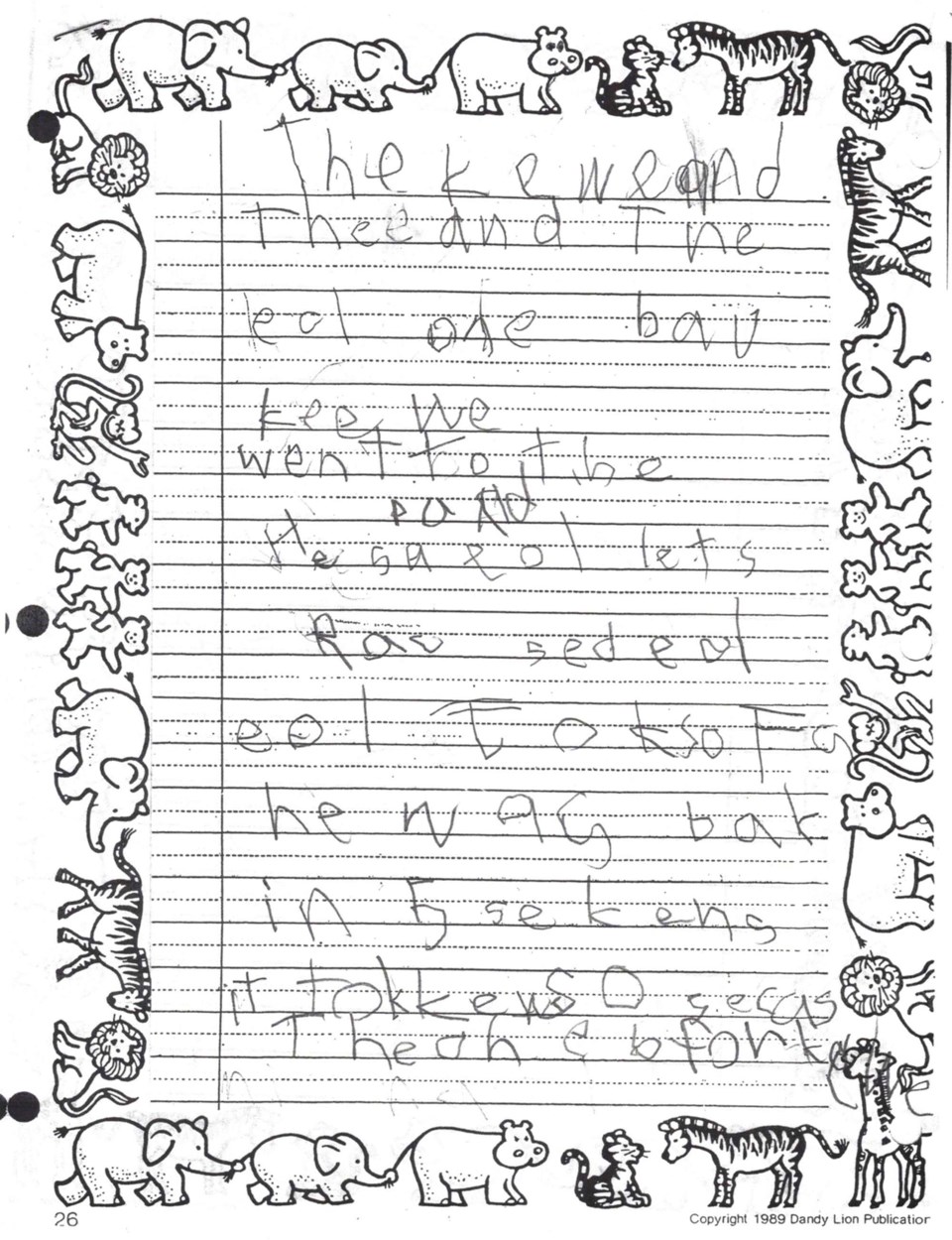

When Tyler was in Grade 3, he needed to write a half-paragraph story. The teacher gave students two weeks to complete it.

“Tyler had written one sentence very poorly ... really messy. That was it. [The teacher] said, ‘Can you just get him to do this at home?’” said Brown.

Brown had Tyler tell her the story while she wrote it out. She stopped him at page 13.

“[Tyler's] true potential to create a story was amazing. But his ability to write it out was zero,” she said.

Hurd said the diagnosis for DCD is tricky because it is “kind of a diagnosis of exclusion.”

“Which means you want to make sure that there's nothing else contributing to what you're observing in terms of their motor development,” explained Hurd.

Hurd said they have standardized tests they use to rank fine-motor skills and balance activities against other children in their age group. Physiotherapists don’t diagnose the condition; that’s what a physician would do.

It wasn’t until Tyler was in Grade 6 that he was officially diagnosed with DCD.

“It took me a while to even figure out once we knew he had dyspraxia, how does being clumsy affect your ability to write in class? It took a little bit of evolution for me to understand how dyspraxia ... impairs planned motor activity. Well, forming a letter of the alphabet is a planned motor activity. Bingo, that's what the problem is,” she said.

Once the Browns got the diagnosis, it became easier to understand what Tyler needed to succeed. Brown said she worked with Tyler extensively to help him get through school.

He also had accommodations. He did not have to take notes or write answers in tests — he was given an aide who could help him by verbally reading the test and then writing down his answers.

As a physiotherapist, Hurd said they identify what issues the child is having and what might be contributing to them, and then they start to break things down.

If a kid has a tough time catching a ball, the physiotherapist won't start by throwing something at them.

“It's more like breaking it down to like, ‘OK, you stand here, and we'll use like a big ball and I'll count down,’ so we have other cues — we're learning where to position our body for that and then we can move on to progressing that in other ways,” said Hurd.

Hurd said it takes time and it can be frustrating for the whole family to work through motor co-ordination issues. It is important to talk about goals and expectations.

The real work, however, happens at home, “... finding ways that work in the home with the family to make it fun. Purposeful play is like finding ways to challenge your child, but also ensuring that you're all kind of engaged is really important.

“It can take quite a while to develop some of those motor skills, especially when you're having trouble with them.”

DCD can also affect non-motor skills in individuals. Memory, perception, processing, planning, organizing, and carrying out tasks can also be difficult for people with the disorder.

In an email written by his mother, Tyler said it feels like his mind and body are fighting against him when he tries to do something.

"If it comes across as if someone with dyspraxia is lazy, that's not necessarily the case; sometimes it's just that performing basic mental functions — and especially motor functions that are not committed to muscle memory — can be much more exhausting than they are for a "normal" person," he said.