The Carbon Challengers

Global heating is a major challenge to the way Albertans live, but it’s a challenge Albertans are rising to meet with new ideas for more sustainable, profitable lives. Twice a month, The Carbon Challengers will profile an Edmonton-area resident who has a cool idea to help keep the planet cool.

Do you know a carbon challenger? Email [email protected] with the details.

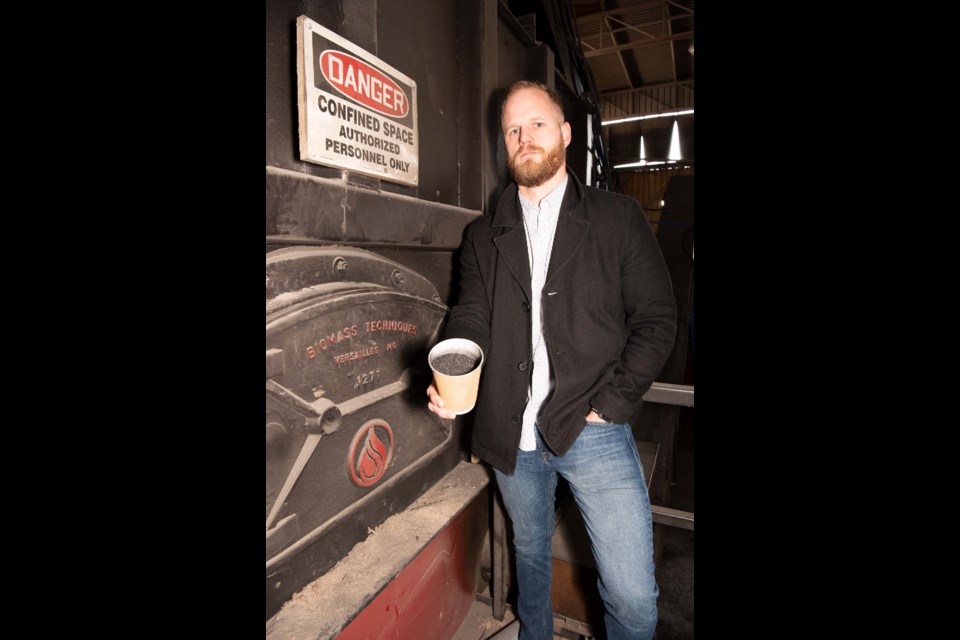

Eight years ago, Chris Olson had his first encounter with a form of black carbon that could help save the world.

Olson, who grew up in St. Albert, was studying alternative energy systems at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology when he first learned about a black, charcoal-like substance called biochar.

“I was working for a waste-hauling company,” he said, and he realized much of the waste wood they were hauling could be converted into lighter, more compact biochar instead of being sent to the landfill to rot.

That resulted in an eight-year journey that continues today, as Olson sets out to address one of the biggest challenges the world faces: how to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions without wrecking our way of life.

“I believe there’s a lot of value we have in these waste streams we’re not utilizing,” Olson said, and he sees opportunity in this technology.

Albertans face major changes ahead as we seek to shrink our carbon footprint and fend off global heating. But some are rising to this carbon challenge with new, sustainable, and profitable ways for us to live, work, and play.

Twice a month, The Carbon Challengers will profile an Edmonton-area resident who has a cool idea to help keep the planet cool.

Biochar’s promise

Olson tugs open the heavy steel doors of a warehouse at the All West Demolition yard in Edmonton. Inside is the biochar machine he and his team have built to try and turn All West’s wood waste into wealth.

The machine itself is more or less a giant oven that turns wood into biochar through pyrolysis.

Pyrolysis is what happens when you heat something up to about 400 C in a low-to-no-oxygen environment. The heat cooks the material without combusting it, resulting in a chunk of solid carbon and gas you can burn for heat.

Biochar, which can be used as animal feed, a soil amendment or a coal substitute, is one of the few technologies that can actually remove and trap greenhouse gas emissions from the air, said Rob Lavoie, the founder of the Calgary biochar marketing company AirTerra and someone familiar with Olson’s work. Unlike a tree or a plant, biochar takes centuries to decay, trapping carbon within it for thousands of years.

“You’re actually creating a carbon sink,” he said, in that you’re sucking carbon out of the air and putting it back in the ground.

Lavoie said the International Biochar Initiative has estimated that about a billion tonnes of char could be produced worldwide by 2060, trapping about 10 per cent of today’s human-caused greenhouse gas emissions – a huge slice of the carbon pie.

Olson said this biochar machine is different from the big green one the Gazette profiled a few years back in that it’s a two-part system. Instead of using propane for its initial heat, he and his team are using a big black gasifier to turn low-grade wood waste into hot gas, which they then pipe over to a rotary kiln (which looks like two black bus-length tubes in a box) that cooks high-quality wood waste. Once operational, this setup should convert about two tonnes of waste wood into 500 kg of biochar an hour and potentially remove some 20,000 tonnes of CO2 from the air a year – the carbon equivalent of not burning 110 railcars of coal, the U.S. EPA reports.

Chris Landry, general manager of All West, said he’s excited by Olson’s setup, as it could potentially keep 16,000 of the roughly 18,000 tonnes of material his crews collect each year out of the landfill.

“If they can get this process working and turn (that waste) into something else, to me, that’s a win.”

Biochar’s challenges

But Landry said it all still has to be affordable, and Olson will have to prove that this system saves All West money compared to landfilling this waste.

“At the end of the day, companies need to make money.”

Olson said policy is key to the success of biochar. Governments need to raise tipping fees at landfills to make waste diversion more attractive, as landfilling is still very cheap in Alberta.

Lavoie said there is also very little biochar made in Alberta right now – a few thousand tonnes a year, tops – and that makes for high prices and low consumer awareness. Government support in the form of contracts to use biochar and field trials to prove its worth would be vital to kick-start the industry’s growth.

Olson said government backing is also essential for research and development – his work has received financial support from Alberta Innovates.

Olson said he hopes to have this biochar machine operational in a couple of weeks and to be selling material from it within a year.

It’s incumbent on all of us to help mitigate global heating, he said, when asked why he’s stuck with this project for so long.

“I think it has a lot of benefits for humanity, and I want to do my best to be a part of that.”