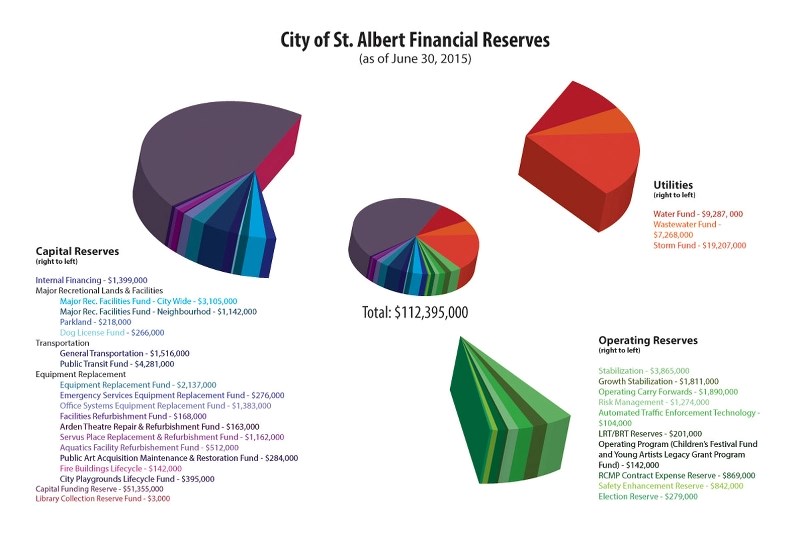

In a commitment to reducing its debt, the City of St. Albert has been steadily moving toward a pay-as-you-go model, racking up $112.4 million in reserve funding, as of June 30, 2015.

While the intent to bring St. Albert back to black is honourable, some question the fairness of higher taxes and the recent spike in utility fees.

Outside of federal and provincial grants, which municipalities are continuously trying to come by, there are two ways of funding capital projects: saving or borrowing.

Over the years, St. Albert has adopted a debt-averse policy, meaning the bank is always the last stop on the search for available capital dollars.

Instead, the municipality has set up 38 different reserves – 13 operating, 21 capital and four utilities – from which it can pull necessary funds.

Other than $23 million in off-site levy funds, which is currently sitting in the Capital Fund reserve, every dollar is earmarked for a specific purpose.

While current mayor Nolan Crouse argued that paying cash out of pocket is the wiser of the two practices, as it reduces the amount of interest taxpayers must cover through taxes, his predecessor and former University of Alberta economic professor, Richard Plain, does not see it that way.

On average, St. Albert has higher taxes than many other municipalities.

In part, this is due to the city trying to pay down its debt from previous infrastructure projects, such as Servus Place and Ray Gibbon Drive, as quickly as possible to avoid paying too much interest.

“We’re trying to bite the bullet so that we don’t have interest in the long term, because interest is very expensive,” explained Crouse.

Last year, the city paid $2.4 million in interest. This year it expects to pay a little more than $2.2 million, as it continuously increases the debenture-servicing amount every year. Currently the city owes $47.4 million in outstanding debt.

Plain argued that despite the large amount of interest, debt financing more evenly disperses the inter-generational tax burden.

Crouse said the opposite is also true.

“If you borrow money to do something, you’re still transferring the responsibility to the future. It still will be the future generation paying for today’s benefits,” said Crouse.

“We borrowed money, for example, to build Servus Place; we borrowed money to build Ray Gibbon Drive. Today’s generation and the future generation are paying for it. The question that’s being asked of reserves: if you collect money today, shouldn’t the future generation pay for that? Well, they’re basically going to collect money for the next generation and the next generation is going to collect money for the (one after that.)”

Crouse added he does recognize the other side of the argument.

“I guess with low interest rates you could argue that (borrowing) is the correct policy,” he said.

Plain said a city needs the right mix of grant, reserve and debt financing and that shifting too far toward one type can cause inequities such as the spikes in utility fees experienced earlier this year.

Last year, the municipality decided to redirect provincial Municipal Sustainability Initiative funding toward capital projects, rather than offsetting the cost of utility fees as it had done in the past.

Plain questioned how the city can charge residents for storm water, calling it a “great injustice” since the city is the biggest user of the system.

Diane McMordie, director of finances and utilities, said that the city is working out a rating system that would take into account the runoff of each household.

Plain also pointed out that it’s easier for the city to pass capital projects when they use provincial grants, such as MSI, rather than debt financing. Municipal borrowing bylaw requires the question to be put to the public if the capital expenditure will significantly increase taxes.

He wondered if this might mean the next Servus Place will be approved quietly rather than aired out publicly with taxpayers.

Crouse agreed that eliminating the politics of borrowing will certainly make the next council’s life easier, but said he does not believe anyone would abuse the system to push through their own agendas.

He also argued that the same public scrutiny could apply to the way the city saves its money.

“If you would have collected the money upfront, you would have had the public scrutiny beforehand and then you would have paid cash,” Crouse said, speaking hypothetically about paying for Servus Place out of a reserve.