Life on Earth is on the ropes.

That’s the main message of a 1,500-page report set to come out later this year from the UN-backed Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), a summary of which came out this month. Written by hundreds of scientists and based on tens of thousands of reports, it’s the most comprehensive study of the state of the world’s biosphere ever produced.

The report finds that, due to human economic activity, more species of plants and animals are threatened with extinction now than at any other time in human history. Up to a million species are at risk of extinction, some of which could vanish within decades.

“Biodiversity is important for human wellbeing, and we humans are destroying it,” outgoing IPBES chair Robert Watson said in a press conference.

We rely on healthy ecosystems for jobs, food, fuel, medicines and enjoyment, and our actions are taking a blowtorch to those systems, the report found. We’re draining wetlands, chopping down forests, overfishing oceans, and polluting the air and water, all of which is causing species to go extinct at rates tens to hundreds of times faster than they have in the last 10 million years.

“If we want to leave a world for our children and grandchildren that’s not been destroyed by human activities, we need to act now,” Watson said.

The report is both a wake-up call and action plan. It identifies the top five threats to the world’s ecosystems – land use, overexploitation, climate change, pollution and invasive species, in that order – and calls for “transformative changes” to address them.

By acting as both individuals and citizens, we can stop these five threats and help save life on Earth.

Invaders and polluters

Invasive species are ones that rage unchecked in absence of their natural predators. Take the mountain pine beetles chewing through Alberta’s forests and forest industry, for example, and the flowering rush choking Isle Lake. The number of invasive species in the 21 nations with detailed records has jumped 70 per cent since 1970, the IPBES report found, primarily due to human activities.

St. Albert has no shortage of invasive invaders – remember those goldfish in Lacombe Park Lake we poisoned in 2018? Garlic mustard has been running rampant throughout the city’s forests since 2010. City of St. Albert arborist Kevin Veenstra and his crew were in the Forest Lawn Ravine last week using steam jets and their bare hands try and beat it back.

“Every one plant produces 700 plants next year,” he said, and each one changes the chemistry of the soil to make it hostile to anything not garlic mustard – including trees. That means less habitat for the animals we enjoy and more expensive weed-pulls for Veenstra.

These invaders are here because we let them loose from our homes and yards. The simplest action we can take on this front is to not let those species loose. Don’t plant species on the province’s prohibited noxious list (which the city publicizes), and report them to the city if you spot them, Veenstra said – he could also use a hand pulling them, if you want to join one of his weed-pulls this summer. Don’t toss your pet fish in the lake (use the trash instead), and clean, drain and dry your boat before you leave waterways.

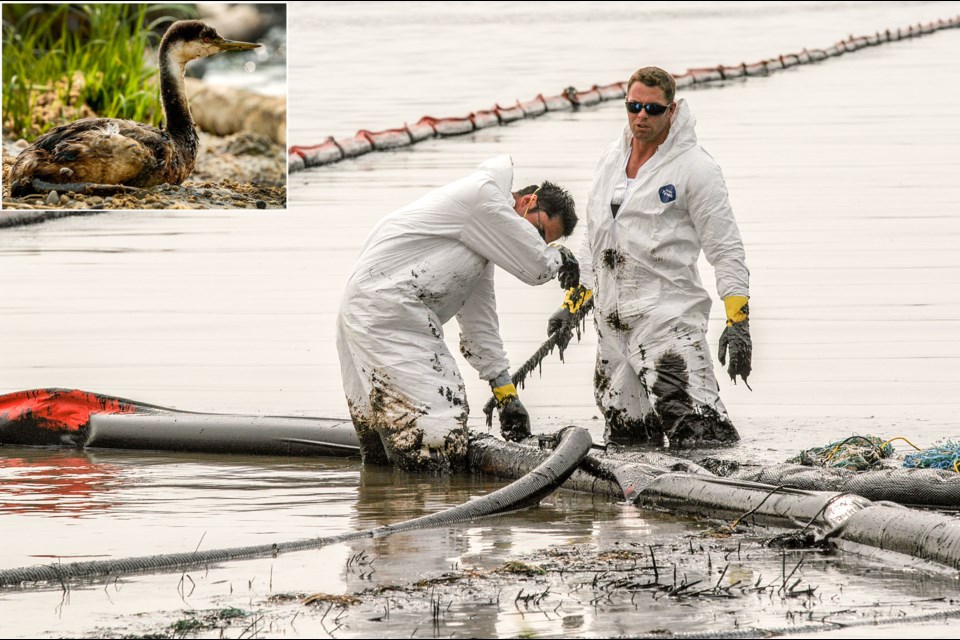

Pollution is a direct result of consumption. More fuel consumption means more heat-trapping pollution from transportation, for example, as well as more risk of bird-killing oil spills. The IPBES report found that we now pull some 60 billion tons of resources from the natural world a year – twice what we took in 1980 – to feed our demand for stuff, and dump some 350 million tons of toxic waste into the world’s waters in the process.

One emerging pollution threat is plastics. The IPBES report found a tenfold jump in marine plastic pollution since 1980, which now affects 86 per cent of marine turtles and 44 per cent of seabirds.

Only about 10 per cent of plastic waste is actually recycled, said Melissa Gorrie of Waste Free Edmonton. The rest blows off landfills into our rivers and oceans, where it breaks down into microplastics that end up in drinking water or the stomachs of birds. A 2015 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimated that some 90 per cent of seabirds had plastics in their bellies.

“They end up starving to death,” Gorrie said, as they have stomachs full of trash.

Recycling and reusable mugs and bags help, but we need to get political to really stop plastic pollution, Gorrie said. That means lobbying for bans on single-use plastic items such as straws and bags, and extended producer responsibility laws that force manufacturers to take back or pay for proper disposal of their plastics.

Climate and consumption

Climate change is currently the third biggest biodiversity threat, but it’s poised to become No. 1 in many ways due to its rapid pace and ecosystem-wide effects, the IPBES report found.

Fossil fuel consumption is what’s driving climate change, said Godo Stoyke of Carbon Busters. Burn coal, gas or gasoline, and you release heat-trapping pollution in the form of carbon dioxide, which warms the atmosphere and turns oceans acidic. More warmth means less ice for polar bears to live on and more mountain pine beetles surviving winter to destroy Alberta’s forests. Acidic oceans kill corals, meaning fewer homes for fish and less flood protection for our cities. We’ve already lost about half of our live coral cover since the 1870s, and will lose all but one per cent of it if we let climate heating hit that supposedly “safe” level of 2 C, the IPBES report found.

Stoyke said you can do your part on climate change by subscribing to green power, which can eliminate all heat-trapping pollution from your electricity use for about $25 a month. You can also draft-proof your home, switch to LED lights, drive an electric car, or take any number of other energy-and money-saving measures.

But what’s really needed at this point is more action from our leaders, Stoyke said. Ask your local leaders what they’re doing about the climate crisis, and lobby for measures in the U.S. Green New Deal, such as its push to get all energy from renewable sources within 10 years.

“That’s the kind of aggressive action we need to take if we want to get a handle on this,” Stoyke said.

It makes sense that land use is the top threat to biodiversity, said Brad Stelfox, a landscape ecologist at the University of Alberta who has studied land use changes in Alberta for 35 years. When you keep converting huge chunks of Alberta into cities, roads, cut-blocks and farms – we’ve used 18 million of Alberta’s 66 million hectares for crops and grazing alone – you shouldn’t be surprised when your numbers of swift foxes, burrowing owls and other endangered species start plummeting.

Land use is directly linked to threat No. 2, overexploitation, by food. The IPBES report found that humans use more than 33 per cent of the world’s land and a mind-boggling 75 per cent of its freshwater for crops and livestock.

Demand for food, particularly ruminant meat (beef), is a major driver for land-use change, said Timothy Searchinger, a research scholar at Princeton University. Something like two-thirds of the world’s farmland is now dedicated to feeding cows, sheep and goats, and much of that farmland used to be forest.

The IPBES report found that about a quarter of the word’s heat-trapping pollution was caused by food production. Eat less meat, and you preserve more habitat and cause less climate heating and fertilizer runoff.

There are a whole bunch of little things you can do to reduce the harms of land-use change, Stelfox said: buy less stuff, walk, bike, live in a compact city, etc. Calling on leaders to take a comprehensive look at land use through the Alberta Land Use Framework is another.

Transformative change

But to really protect life on Earth, we need to take on the big boss behind the big five: the structure of the global economy itself.

Stelfox and the IPBES report note that the biosphere is in the mess it’s in now because we have an economic system that ignores environmental costs and encourages unsustainable production. We subsidize fossil fuels to the tune of $345 billion a year, for example, despite the fact that those fuels cause some $5 trillion a year in harm to ecological services.

“We need to evolve our economic system to better reflect the adverse effects we’re having on the environment,” Stelfox said.

One solution is to change the goal of the game, said Kai Chan, a sustainability science professor at the University of British Colombia and a lead author on the IPBES report. Instead of just measuring success based on profit (i.e. GDP), we can call on our leaders to actually account for the cost of environmental harm when evaluating economic decisions. The Genuine Progress Indicator is one of many GDP alternatives that account for such costs. Factor in environmental costs, and a whole lot of our current rules and subsidies no longer make sense.

Chan said our job as citizens is to demand our leaders take the environmental challenges before them seriously and make the changes we need to have a sustainable economy, which is what all the actions listed above aim to create. He suggests signing the Citizen’s Call for a Global Sustainable Economy at Change.org as a starting point.

There’s a lot for us to do if we want to preserve biodiversity, but a long list of benefits for doing so. IPBES has previously calculated that nature provided Canada with some $3.6 trillion in ecosystem services a year.

If life on Earth is in trouble, so are we. Protecting biodiversity isn’t just about saving the animals; it’s about saving ourselves.