There they were, Father Albert Lacombe and Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché, standing on a hill overlooking a lustrous, snow-covered river valley in the middle of winter. It was Jan. 14, 1861.

There they were, Father Albert Lacombe and Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché, standing on a hill overlooking a lustrous, snow-covered river valley in the middle of winter.

It was Jan. 14, 1861. The two men were discussing the establishment of a new mission. Lacombe explained how fertile the land was and how the location was right. It was a good stopping point between Fort Edmonton and Lac Ste. Anne. Families were already established there.

Taché agreed, stamped his walking stick to the ground and the mission that would eventually become the city of St. Albert was born.

This year Mayor Nolan Crouse started a new tradition of proclaiming Founders’ Day to acknowledge that occasion, whose story is familiar to many residents.

But does the average resident really know who Lacombe and Taché were as people? What kinds of families did they come from? Did they have nicknames? Did they get along? Who were these two individuals, besides being Oblate missionaries – one a father and the other a bishop?

Some of these lesser-known details can be gleaned from the numerous books that have been written about these two founders or from talking to various local experts.

Father Albert Lacombe – a builder of bridges

Albert Lacombe was born on Feb. 28, 1827 in Saint-Sulpice, a small community settled by French immigrants on the north banks of the St. Lawrence River. He lived and worked on his family farm but didn’t want that life for himself. He had an early interest in religion, but had many plans, wrote longtime friend Katherine Hughes in the biography Father Lacombe, the black-robe voyageur, published five years before his death.

In the book, Hughes states that in his youth, Lacombe yearned to be out in the world, not feeding the pigs and driving the plow.

“The boy’s heart in him was burning to leave the farm, to go to college to be a great man, a priest maybe like the old curé, Monsieur de Viau; or perhaps to leave books altogether and like his grand-uncle, Joseph Lacombe, to go far into the Pays d’en Haut with the fur-company and be the most daring voyageur of them all. Either career seemed blissful to the boy, for these two men were the heroes of his childhood.”

The priest, the passage continues, dubbed the boy, “mon petit sauvage (my little Indian),” because Lacombe’s mother had Ojibway blood in her heritage.

Hughes said Lacombe was always emotional. When de Viau offered to pay Lacombe’s way through college, he was speechless and could only thank the old man with tears in his eyes.

In response, de Viau stated, “Who knows? Some day our little Indian may be a priest and work for the Indians!”

Lacombe would realize both of his childhood dreams, first by being ordained at the age of 22 with the Catholic missionary order, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. Soon thereafter, he would travel west to work in North Dakota before returning to Canada in 1851 to take the position of vicar at Berthier. In 1852, he met Monsignor Alexandre Taché and followed him to the Red River Colony in Manitoba and points beyond.

He would stay in the west for the rest of his life.

Diane Lamoureux, the local archivist with the Oblates, said Lacombe was important to more places than just St. Albert. His reach stretched far and wide.

“He established other communities. He was on the Treaty Commission for Treaty Eight in 1899. He went to the Ukraine and was involved with the Galicians (Ukrainian Catholics) coming into Alberta. He created a French Cree dictionary that was published in 1876. Probably the thing he’s best known for is the pictorial catechism that he created,” she said.

He was also famous for his bridges, and not just the ones that span rivers. In addition to getting St. Albert the first bridge west of the St. Lawrence, he was also a driving force for bridges in other communities, and between peoples. When an aboriginal woman was taken captive by a warring tribe, he bartered for her return.

“He had to buy her. I think he had to give up a horse. He also negotiated with the aboriginal people to allow the railway to pass through their land. As a result, he was given the honour of being the chairman of CPR for an hour,” Lamoureux said. “He had an honorary rail pass that was given to him until his death.”

Lacombe was also widely regarded as a friendly soul, earning the nicknames “Kamiyoatchakwêt, the noble soul” by the Cree and “Aahsosskitsipahpiwa, the man with a good heart” by the Blackfoot.

Lacombe struggled with health issues related to his kidneys and bladder for decades. He was 88 when he died in late 1916 after working tirelessly his entire life.

His body was interred in the crypt at the St. Albert Parish but not before – according to his wishes – his heart was removed. The heart was kept in a glass urn until recently when it was buried on the grounds of the Father Lacombe Care Centre in Midnapore in southern Alberta, his home for the last several years of his life.

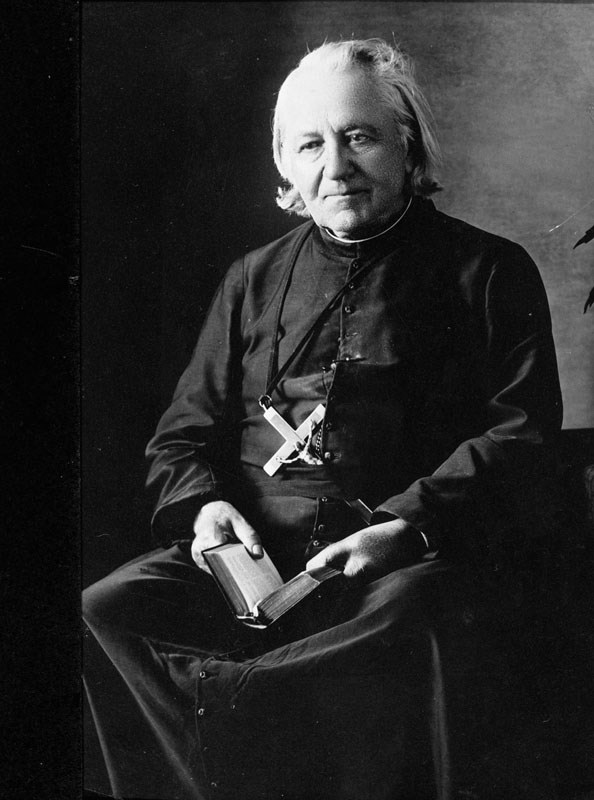

Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché – French to the core

Like Lacombe, Bishop Taché was a pious man who did much and travelled far.

“Until the diocese of St. Albert was erected, the diocese of St. Boniface covered basically all of the Northwest Territories,” Lamoureux said. “He traveled extensively from St. Boniface through the north and what is now Alberta, which is how he ended up in St. Albert on that January day in 1861 with Father Lacombe.”

Taché was born in 1823 in RiviÈre-du-Loup on the south banks of the St. Lawrence River. He was the son of a merchant and a descendant of famous explorers who helped to create New France itself. His French roots were hearty as would be proven throughout his life.

After his father’s death, he was raised under his uncle’s care and learned about the arts and other pursuits.

He started to develop his sense of duty to his faith while studying at a seminary when he was only 10. He progressed quickly and was regarded as a keen Catholic who did much for the church. Taché was ordained as a bishop when he was only 28 years old.

“Taché, before he became the bishop, was the first Oblate to establish a mission in Alberta at Fort Chipewyan in 1847. He was, if not the first, then among the very first Oblates to travel into what is now the province of Alberta,” Lamoureux said.

He was called by Pope Pius IX to participate in the First Vatican Council, where papal infallibility was decided. In 1871, he became the first archbishop of St. Boniface.

He was also someone who struggled with interpersonal relationships and other conflicts. He and Lacombe were lifelong friends but many other people took exception to his authoritarian style, wrote Raymond J.A. Huel. His biography, Archbishop A.-A. Taché of St. Boniface – The ‘Good Fight’ and the Illusive Vision, describes Taché as “a noble figure who was simultaneously of heroic and tragic proportions.”

Former prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier called Taché saintly but naïve – in other words, a man devoid of political sense.

Huel added that Taché never truly assimilated to the West, maintaining his devotion not only to the church but also his eastern Canadian francophone heritage.

“The bishop always remained a Quebecer at heart. So deep was this attachment that Taché attempted to reproduce his native province on the western plains by seeking constitutional guarantees for the French language and Catholic faith and by promoting French Catholic immigration to Manitoba and the North West,” he wrote.

Taché died at the age of 70 after a few years of failing health. His remains were interred in a stone vault under the great altar at St. Boniface Cathedral.

Huel makes the following note in his book: “He asked to be buried in his cathedral and indicated that the following inscription should appear on his tombstone: ‘Pray God to pardon him his numerous faults.’”