Yannick Tona says he didn't know his life would change forever on April 22, 1994.

He was sitting with his family at his grandmother's house in southern Rwanda, he recalls, when a mob of 400 people ran down the street. "I had never seen that many people like that," he says. "I thought, 'Wow, this is like a movie!'"

When his uncle stopped one of them to ask about the commotion, the man said, "They've started killing Tutsis in Nyanza [a nearby community]."

Tona was witnessing the Rwandan genocide — a murderous campaign by state-backed militia against ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutu residents that killed some 800,000 people in 100 days.

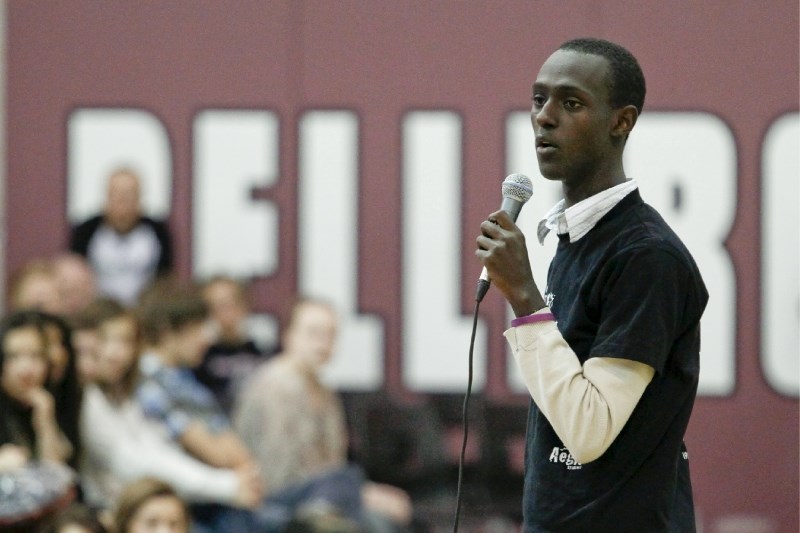

Now 21, Tona spoke before some 700 students at Bellerose Composite High School Friday about what they can do to stop such massacres from reoccurring.

You don't need money or fame to help, he says. "You need one thing: you need to make a choice that you can make a difference in your community."

Stunning tale

Tona, a speaker with Aegis Trust, a group dedicated to preventing crimes against humanity, is the first of four speakers that will visit Bellerose this year to help students connect with world events, said principal George Mentz.

The roots of the Rwandan genocide go back to the days of colonization, Tona says. While his people used to have one language and one culture, the Belgians split them along arbitrary ethnic lines. If you were tall with a long nose, you were a Tutsi. Short and big-nosed? Hutu. These words used to refer to people who were "rich" and "poor," respectively, he notes.

What followed was decades of state-sponsored discrimination by the Hutu majority against the Tutsis. "My dad did not go to high school because he was from a Tutsi family," he says. Others were denounced as inyenzi, meaning "cockroaches."

On April 6, 1994, then-president Juvénal Habyarimana was assassinated when his plane was shot down near the capital city of Kigali. Roadblocks soon popped up throughout the city as militia members distributed lists of Tutsi residents to kill. "The media was encouraging Hutus to kill Tutsis."

The massacre reached Tona on April 22 when that mob of people ran by his grandmother's house. "My family started to panic," he says, and determined that they should pair off, scatter and hide.

It was the last time he would see many of them alive, he says.

He and his mother, who walked with a cane, spent the next three weeks walking to what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo — a seven-hour drive by car. "I'm four years old," he says, and the longest he'd ever walked before was maybe 10 minutes. "I have no idea what's going on."

He and his mother had to make the whole journey without food, he says, as they'd be killed if they went to a market. "I saw bodies everywhere."

Everyone, even close friends, was trying to kill them, he says. "I raised you as my only child," he recalls his mother saying to one man, "and because you're Hutu and I'm Tutsi you're going to kill me?"

"Yeah," he replied. "You are the enemy and you need to be killed."

Choose a better world, he says

Tona and his mother eventually reached the Congo and reunited with his father and sister. Some 16 other members of his family, including his one-year-old brother, died during the genocide.

Seven people a minute were murdered during the genocide, Tona says, many of them children. "They're not animals. They're human beings like us."

Rwanda has since held a Truth and Reconciliation Committee to document the massacre and eliminate its discriminatory policies, he says. "There is no Hutu and Tutsi. We are all Rwandans."

Kigali was declared one of the safest cities in east Africa last year, he says, proudly.

The Rwandan genocide started out as bullying and insults, Tona notes, and he urged students to take a stand against them. "When you see someone bullying somebody, don't watch. Say it's wrong."

He encouraged the students to use their time, money and sympathy to better their communities. "If you don't care, no one cares. It's our responsibility as young people to make a difference."