There’s an old joke about the “fun” in “funeral” that comes to mind when it comes to the Namao Cemetery.

On most days, it’s a quiet place, empty save for the rush of cars on the nearby highway and its rows of graves – each one a summary in stone of a local life lived.

But once a week, so long as the grass grows, the place comes alive as Gordon Carson, Gary Gibson and the other volunteers with the Namao Cemetery Company arrive to mow grass, trim trees, straighten headstones, chat and laugh.

“We gather here every Monday and tell lies and cut grass,” Gibson quipped.

“It beats going to Tim Hortons.”

Carson said there are some 380 people buried in this cemetery, and they’re all pretty happy about it as far as he can tell – they never complain, in any case. A fair number are relatives of his buried in the Carson plot.

“My great grandfather is buried here. My grandfather’s buried here. My father’s buried here, and I haven’t dug my hole yet, but I’m going here,” he said.

Cemeteries are focal points for history, the gravestones within them a physical index to the lives that make up a community’s story. Carson and Gibson are two of the many volunteers that keep these rural cemeteries, and the stories in them, alive.

Whether it’s Dawson City or Yellowknife, a cemetery should be the first place you visit if you want to get a sense of a community’s story, Gibson said.

“In a small way, the Namao Cemetery reflects the history of Namao.”

The cleanup crews

Carson and Gibson say they’ve been volunteering at the Namao Cemetery since the 1980s – Carson after burying his dad there, and Gibson after he was “conned”/convinced to sign up by former volunteer Cliff Crozier.

Robert Lema said he started volunteering with the cemetery group at St. Peter’s Parish in Villeneuve some 50 years ago due to his interest in history. He’s still at it today, and sometimes gives tours of the Villeneuve cemetery’s 300-odd graves to school kids.

“It’s important to me that every person here is remembered,” he said.

Lema, Carson and Gibson said cemetery work involves a lot of trimming trees and cutting grass – a lot of grass this year, given the rain. Sometimes you bring in dirt to fill in dips caused by settling soil or throw a few inches of gravel under a tombstone that’s starting to tilt. Other times you have to sell plots and help grieving families arrange burials. They hire professional diggers now, but prior to the 1970s it was also up to volunteers to dig the graves – a process that involved thawing the ground with coal fires in the winter.

Some cemetery work is more elaborate. Lema said one major bit of maintenance at the Villeneuve cemetery happened two years ago. Many of the older gravesites dated back to a time when people would place large concrete panels over them, and those covers were creating dangerous dips in the land as they sunk. After consultation with area families, the cemetery group arranged to have those panels taken off 60 of the graves.

“We did not move the headstones,” Lema said – instead, crews carefully cut them off the panels and laid them back in place on new concrete runners. That’s why some of the older stones here have rough-hewn bottoms.

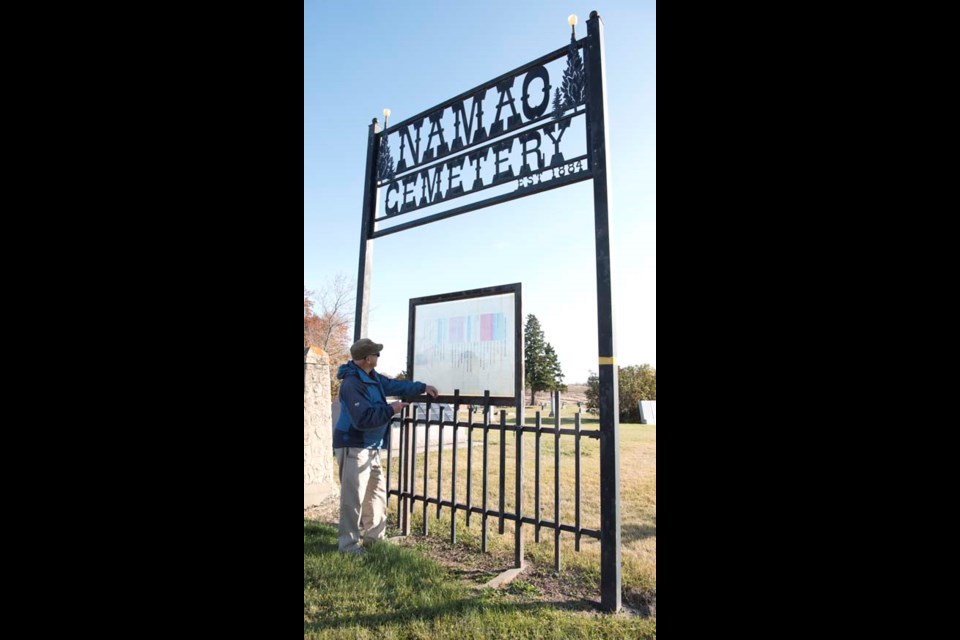

Namao super-volunteer Jack Speers had a hand in many of the more recent improvements at the Namao Cemetery, Carson said. Over his decades of community service, Speers created the cemetery’s grave map, helped organize construction of its entrance sign and maintenance shed, funded its first columbarium, and for many years used his own lawnmower on the grass.

“That man was incredibly tough,” Carson said, who recalls seeing the man swinging a chainsaw to clear out brush at the cemetery well into his 80s.

While Speers himself is buried with his parents in Evergreen Cemetery in Edmonton, many of his relatives reside in the Namao Cemetery, Carson said. There’s also a plaque bearing his name on the cemetery’s memory wall – another Speers idea, meant to honour community members buried elsewhere.

Gardens of history

Carson said the Namao Cemetery owes its origins to Namao’s first settler, Harry Long.

Long passed through this area as part of a crew surveying Western Canada and returned to settle here in 1879, writes historian Bertha Speers. In 1883, he married Libby Whitelaw, a talented musician whose parents insisted on shipping a baby grand piano with her all the way from Swift Current, Sask.

Whitelaw died giving birth to her son, Bert, in August 1884, Bertha wrote. It was the first death in the district, so Long donated a corner of his land to create the Namao Cemetery.

Long laid out the cemetery in exacting detail, using his skills as a surveyor to designate all the needed paths and plots, Carson said. Many of his original survey pins are still in place today. About the only thing he didn’t do was actually register the place with the government.

“We found out that the hard way,” Carson said, and it cost them about $8,000 to address the oversight.

A greying slab covered with grey and orange lichen marks Whitelaw’s grave in the back corner of the cemetery next to a large spruce tree. Long and many other members of his family are buried nearby.

St. Peter’s Cemetery is currently located on the other side of Hwy. 44 from the Villeneuve church, Lema said. That wasn’t always the case.

Villeneuve’s first cemetery was set up sometime between 1897 and 1901 about a mile east of town, as the land around the church (which was originally close to where the Hwy. 633 roundabout is today) was too low and wet, Lema explained. Parishioners buried two people there before they decided it was too far away and set up a new cemetery northeast of the current church site.

The villagers managed about a dozen burials there but ran into trouble in 1901, where just as they were going to lower an old pioneer into the earth they noticed that his grave had filled with water, writes historian Monique Aultman. The body was buried in St. Albert instead, and the community asked Bishop Legal for a new cemetery site. Legal chose the present site in 1907, and the cemetery’s dozen or so inhabitants were moved over the next year.

Persons of interest

You’ll spot a lot of familiar family names if you wander around St. Peter’s Cemetery – Soetaert, Derocher, Berube – many of which reflect the French and Belgian origins of the community’s first settlers, Lema said.

“The most common name in this cemetery is Callihoo,” Lema noted, which reflects the strong ties the Michel Band has to this region. Chief Michel Callihoo donated the logs for the original St. Peter’s church back in 1897 and asked that his people be allowed to worship at it.

While Chief Callihoo is buried in St. Albert, Lema said the chief’s brother Louis and his wife Victoria can be found about 20 metres past the main gate at St. Peter’s. Victoria is notable for being one of the last living participants of this region’s last buffalo hunt.

“She was a great lady,” Lema said, and she lived to an amazing age of 105.

Lema noted there are likely many unmarked graves of Michel band members at St. Peter’s. The easiest way to clear weeds from a rural cemetery prior to the 1960s was to simply light a match, and that would have destroyed the wooden grave markers used by many band members (most could not afford headstones). Markers that survived likely rotted after 20 years.

“It was sad that happened,” Lema said of the destruction, and he’s now working with other historians to build a monument to these lost graves in the cemetery.

You’ll also find a number of unusually small headstones near the front gate.

“These are all children who died,” Lema noted, some of whom lived for just a few days. One stone, which simply says, “Soetaert,” is the size of a nameplate and barely visible in the grass. This was likely for someone who died in childbirth without a name, Lema explained.

Places of peace

Cemeteries are full of history, and Lema said he makes it a point to visit local ones whenever he goes travelling. As a Catholic who believes in the afterlife, he also sees them as places to remember and respect those we loved.

“The people are dead, yes, they’re gone, but their spirits are alive.”

While most of the Namao Cemetery volunteers are getting on in age, Carson said he is confident others would step up to care for this place when he takes up permanent residence in it.

“I just hope Gary will cut the grass over me and not let it grow!” Carson joked.