Back around 1948 in a one-room Catholic schoolhouse in Volmer just north of St. Albert, a young John Bocock sat down with his pencil and paper to write about what he wanted to be when he grew up.

Back around 1948 in a one-room Catholic schoolhouse in Volmer just north of St. Albert, a young John Bocock sat down with his pencil and paper to write about what he wanted to be when he grew up.

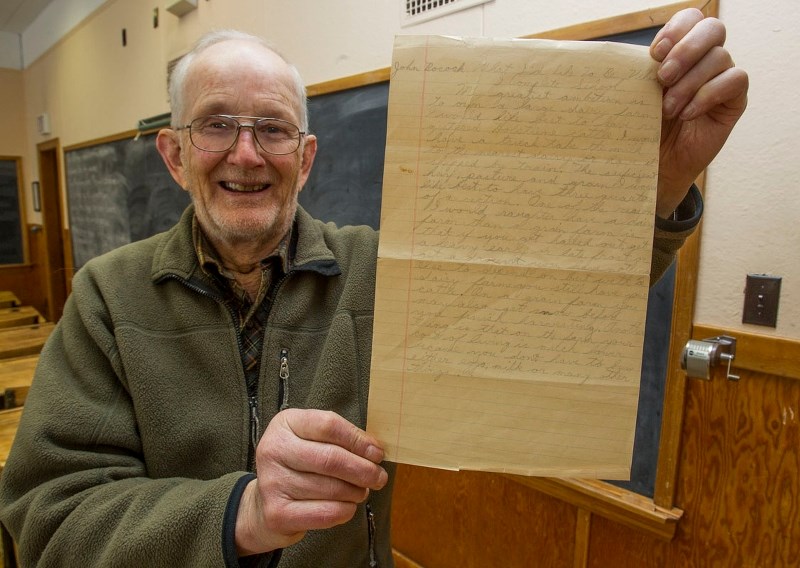

"My greatest ambition is to own a large dairy farm," he wrote, in smooth, cursive script – specifically one with registered Holstein cattle.

Now a retired dairy farmer, Bocock still has that piece of paper. Volmer and the school are long gone, but Catholic education in the St. Albert region is still here.

The schools have changed, of course – they have running water, for example, as well as more smartphones and less memorization, Bocock notes.

"I was rather shocked to hear, I think it was just yesterday, on the radio that they're building classrooms without blackboards," he says.

Catholic education in St. Albert began some 150 years ago this year. To celebrate, the Gazette takes a look back to where it all began, and peeks ahead at what might come next.

In the beginning

It was Marie-Jacques Alphonse of the Grey Nuns who first brought Catholic education to St. Albert, serving as teacher to the seven orphans. Although the nuns arrived here (and presumably started teaching) in March 1863, they didn't have a formal place to teach in until September 1864.

That place was the convent on Mission Hill, says historian Ray Pinco – a place that would continue to host students as late as the early 1900s.

"Conditions would have been pretty meagre," he said, with little furniture, perhaps slates for writing, and windows made of cotton (glass was expensive).

The curriculum would have covered English and French grammar, arithmetic, and practical skills such as woodworking or gardening with an emphasis on religion and morals, reports the Black Robe's Vision.

"For individuals to get what we would consider today a high-school education was pretty unusual," Pinco says, with most dropping out after two to four years of school. Attendance was poor, as students often had to head home to help at the farm or on bison hunts.

Many of the teachers had strong credentials, however, with Sisters Shara Dillon and Marie des Agnes becoming the community's first certified teachers in 1888, the Musée Héritage Museum reports.

The students were also high achievers, with students of the industrial school (see below) winning certificates in blacksmithing, carpentry and crafts at the 1893 World's Colombian Exhibition in Chicago. The school's band even played at the 1905 inauguration ceremony for the province of Alberta.

Students moved into a larger two-storey seminary on Mission Hill by 1880, reports the Black Robe's Vision. An industrial school aimed mainly at aboriginals joined it in 1895.

By 1898, the St. Albert Roman Catholic Public School District No. 3 (est. 1885) hosted about 285 students.

A century ago

George and Ed Poirier built St. Albert's first dedicated school building in 1910.

Officially named Father Mérer School after a local trustee, the four-room, two-storey building was called the Brick School by pretty much everyone and stayed in operation until 1958.

"As you walked in the front door, facing you was this huge staircase," recalls Pinco, who attended it in the 1940s. Classrooms were to either side.

At the front of each class was a large blackboard with doors on either side leading to the cloakroom, he recalls. Tall windows to your left provided light to supplement the bare bulbs above.

The floors were wood coated with linseed oil, while the desks were wood and iron. A ceramic jug with a spout provided drinking water, and a coal furnace provided heat. When the furnace failed in the winter, your inkwells froze.

"If it wasn't fixed by about 10, we were told to go home," Pinco says.

Classrooms were often extremely overcrowded, with 50-kid split-grade classes not uncommon, Pinco says.

When Bocock arrived there for Grade 12, things were so cramped he had to take his lessons in the cloakroom.

"I proudly proclaim to anyone who's interested that I graduated out of the girls' cloakroom," he says.

Bocock says he and his siblings typically walked, biked, or rode horses to school when they went to Volmer. Bus service to St. Albert kicked in when he started high school.

While slacks and dresses were common in big city St. Albert, Bocock says country students preferred blue-jean overalls.

Recess fun consisted of softball, "throw the ball over the school," and hunting gophers.

You'd flood the gophers out with water and bash them with a bat, Bocock says of the latter.

"Animal rights weren't such a big issue in those days."

50 years back

Overcrowding led to a number of new schools in St. Albert, including the Little White School, the one-room "chicken coop," and, in 1953, the St. Albert High School (now known as the NABI building on Mission Ave.)

The high school had linoleum floors, green blackboards, a gym, a shop class, a home-economics room, and even a pseudo-science lab and library, Pinco notes – most previous schools had barely managed a single bookshelf.

Post-secondary education was still fairly uncommon in these years, with most students dropping out at age 15, Pinco says.

"In those days, you sat down, shut up and listened," he says – and if you didn't learn, you repeated the grade.

Students also got to play with all sorts of dangerous substances in class, including bleach, mercury, and asbestos powder (for sculpting), he chuckles.

"And this was sanctioned by the department of education!"

The next few decades saw a flurry of new schools built in St. Albert, including Albert Lacombe in 1964, VJ Maloney in 1973 and Bertha Kennedy in 1976.

Technology marched on as well. The photocopier replaced the mimeograph (which used ink and stencils), and made for much less copying from the board for students, Pinco says.

The 1980s saw the arrival of the first classroom computers. Former Albert Lacombe principal Leo Bruseker recalls selling spices as a fundraiser to buy just one Apple IIe computer, which cost about $2,400 at the time (about $5,400 today).

"We had the gym full of spices," he says, and you could smell them everywhere in the school. People could buy coffee-can-sized sacks of bay leaves – a lifetime's supply, he jokes.

"It could become an heirloom!"

Attitudes in school also evolved, he continues. The strap fell out of favour in the late 1980s, and staff started taking student safety seriously, requiring parents to report absent students and locking doors during school hours.

Towards tomorrow

Today the Greater St. Albert Catholic district hosts some 6,000 students in 16 schools. Smartboards have replaced blackboards, and the Internet has replaced the encyclopaedia.

Most people asked by the Gazette were at a loss when asked to envision Catholic education 150 years from now.

It will still be Catholic, but it will also be much more flexible and student-centric, predicts Catholic board superintendent David Keohane.

"150 years later, our system continues to grow."

Students of tomorrow might not even go to a formal school building, speculates Sandra Fildes, who taught at Albert Lacombe from 1977 to 1990 – they could just video-conference from home.

"I hope not, because the schools and the community of a school is so valuable for social interaction."

One thing that won't change in the next 150 years will be the students, Fildes and Bruseker agree. They'll still be curious, they'll still need to be active, and they'll still need guidance from adults.

"Kids will still be the same," Fildes says.